Free Speech, respectability politics, and the the Safe for Work Self

Or, the Free Speech Union gets it right for a change

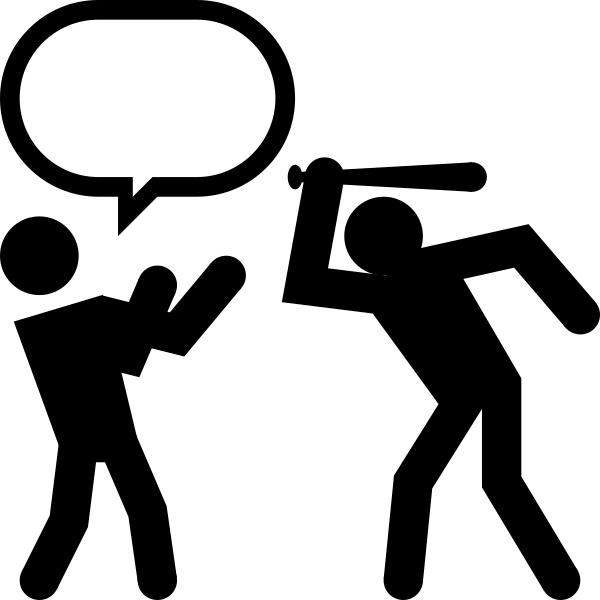

It would be fair to call me a critic of the Free Speech Union (FSU). The organisation functions largely as an event management company for touring far-right and transphobic speakers, not just supporting the right of these people to speak on principle, but actively assisting them in spreading hateful rhetoric. The FSU is also in the process of a hostile takeover of Internet New Zealand in response to the non-profit becoming more Te Tiriti centred. Much of my criticism of the FSU comes from the fact that their activism rarely seems to acknowledge that suppression of free speech comes from the threat of violence (both structural violence like the threat of incarceration, and interpersonal violence such as death threats) and is a product of unequal power relations.

Aotearoa (not unlike elsewhere) has a well documented problem of harassment being used to silence people, especially women and people from marginalised groups. This is also a free speech issue, but the FSU has, at best- ignored it, and, at worst- advocated for legislative change that would help the harassers.

Last year I attended a conference of the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR) and the words of Shih-Diing Liu, a Professor of Communication at the University of Macau, have stuck with me since. Liu noted that "the social order is about who can speak in the public sphere, and who can not".

On May 20th, Minister of rail Winston Peters (at that time also the Deputy Prime Minister), was giving a press conference with transport minister Chris Bishop about upgrades to the country’s rail network, but he was also asked about potential punishments for Te Pati Māori MPs’ ‘disruption’ during the vote on the Treaty Principles Bill by performing a haka. Peters said the MPs had treated the Parliamentary protocols with "absolute contempt". A passerby responded by yelling "what a load of bollocks". Peters fired back "Who said bollocks? You look like bollocks, go look in the mirror, sunshine. You look like bollocks, mate," the man then called Peters a "tosser". Peters responded telling him to "naff off".

The man on the street was speaking truth to power, regardless of what you think of his choice of words. It’s the latest addition to the ongoing public debate over what is sometimes called ‘respectability politics’; Is a haka in parliament appropriate? Can you tell the Deputy Prime Minister he’s talking bollocks? Can a journalist call a female minister a cunt?

In an article published in the academic Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Mikaela Pitcan, Alice E Marwick, and danah boyd define respectability politics thusly:

“Respectability politics reflect neoliberal, White, bourgeois normativity, and provide a frame for understanding subordinated group behavior from a gendered, classed, and racialized perspective. Respectability politics reinforce designations of appropriate or inappropriate behavior rooted in structural inequality. Moreover, the process of deeming an act respectable is reflexive. Those enacting respectability respond to their perception of the dominant narrative of respectability, and this response informs ideas of what is respectable. In other words, by privileging racist, sexist, and classist values, respectability politics lead members of subordinate groups to internalize them.”

The employer of the man who heckled Peters, engineering company Tonkin + Taylor, issued an apology, and publicly revealed that a code of conduct investigation was underway. “At Tonkin + Taylor we take our responsibilities as a major New Zealand employer seriously. We do not condone behaviour that falls short of our code of conduct.” Peters turned to respectability politics when pushing back against the framing of the incident as a free speech issue “I’ve never heard such filthy language out in the public like that – foul, filthy language – and if you think that’s free speech, you couldn’t be more wrong,”

To their credit, the Free Speech Union had the right response. “Individuals don’t give up their speech rights when they accept a job," said the FSU’s Nick Hanne in a press release.

“The company apologising off the bat sets a dangerous precedent, sending a message to employees that expressing political opinions in public is unacceptable … We’re contacting Tonkin + Taylor, urging them to respect their employee’s speech rights, and not to set a poor example to other Kiwi businesses. Employers should not overreach into employees’ personal lives, dictating what is and isn’t acceptable to say. This would cause huge damage to our democracy.

Arguably, this democracy-damaging overreach is already with us and has been for a long time. In their article (which was published in 2018) Pitcan, Marwick and boyd quote a 25 year old Puerto Rican New Yorker who lives in one of the city’s public housing projects.

“They [privileged people] kind of dictate what’s good to say because we’re trying to appeal to them. Because they’re the ones who have the jobs, and they’re the ones who have the money to give us jobs, so we don’t want to say anything that would … make us seem lesser in their eyes.”

In her 2013 book Status update: celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age Alice E Marwick used the phrase ‘the safe for work self’ to describe the way that in the era of social media an individual must market themself as a salable commodity that can tempt a potential employer. She notes that academics tend to be disparaging of this self-branding:

“They argue that practitioners remake themselves as products to be sold to large corporations, that they rely on an imaginary sense of what employers might want, and that they sully personal feelings and relationships with market forces. Self-branding, while widely taken up in the tech scene, is inherently contradictory. It promotes both “authenticity” and business-targeted self-presentation. This incongruity creates tension and stress for practitioners, who must engage in emotional labor and self-surveillance to ensure an appropriate branded persona.”

For most of us, who work for a living, the need to maintain a safe for work self is a barrier to political participation. In the technology sector, where Marwick notes this self-branding has been taken up widely, we can easily find examples of people deprived of their livelihood for lawful political activity. Both Microsoft and Google have fired employees for protesting against the genocide in Gaza. Both companies also provide services for the Israeli government. “Google’s aims are clear,” said Jane Chung, a spokeswoman for No Tech For Apartheid, when the number of Google employees fired reached 50. “The corporation is attempting to quash dissent, silence its workers, and reassert its power over them”.

Tonkin + Taylor has contracts with New Zealand’s government, which may explain their response to an employee heckling the deputy Prime Minister. I reached out to workplace relations spokespeople for the opposition Labour and Green parties. I didn’t receive a response from Labour’s Jan Tinetti in time for publication, but Green MP Teanau Tuiono told me he agrees that being employed doesn’t mean someone forfeits their rights to express political views, and that Tonkin + Taylor disciplining their employee would set a dangerous precedent. “I also worry about the chilling effect this could have on people expressing their opinions.”

“The right to freedom of expression in the workplace is already under attack by this Government. We have the Pay Deductions for Partial Strikes Bill going through the House – this would penalise workers, for example if they wear a t-shirt or badge expressing a political view related to issues in the workplace. Workers should be able to use their collective power to fight for better pay and conditions. What the Government has proposed would make it easier for bosses to dock the pay of staff who challenge the working conditions they are subjected to.”

For some people, losing a job could be a calculated sacrifice deemed worthwhile to be on the right side of history. Software engineer Joe Lopez, who interrupted a speech by Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella to protest the company’s work supplying the Israeli military with technology used for the war in Gaza, probably knew what his fate would be. But it’s not a sacrifice everyone can afford to make. Many working class people will instead be self-censoring their social media, or avoiding attending protests where they may be filmed or photographed by people who would like nothing more than to see them lose their main or only source of income for ‘code of conduct’ violations.

This results in a situation where the people who can opine on social and political issues are the ones who are independently wealthy- business owners and landlords- who will more often than not have interests opposed to those of working people. Another interviewee in Pitcan, Marwick and boyd’s study put it succinctly:

“So, let’s say a person who’s already among […] the so-called privileged class. Let’s say the kid who is heir to a billion-dollar fortune, I think that person has the luxury to say, “Screw it” and just do whatever he or she wants.”

New Zealander Nick Mowbray, the billionaire founder of toy company Zuru, has been extremely vocal in his support of British far-right activist Tommy Robinson, while also taking legal action against Glassdoor (a website where people can anonymously review their employers) in an attempt to force them to give out details of former Zuru employees who’d left negative reviews of their workplace. Returning to those words from Shih-Diing Liu, "the social order is about who can speak in the public sphere, and who can not", working class people are repeatedly being reminded that it is us who can not.