The New Zealand Far-Right and the Right

A speech given at the 50th anniversary of the Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA)

The NZ Far Right and the Right

I was asked by the Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) to speak on the topic of the far-right and the right at their recent 50th anniversary event. CAFCA has, for half a century now, been drawing attention to issues related to privatisation and the buying up of Aotearoa’s resources by multinational corporations. Below is the text of the talk in full.

I was given the topic ‘the far-right and the right’ and what a timely topic that has turned out to be. I was writing an article recently about David Seymour’s response to the assassination of Charlie Kirk. Charlie Kirk was the founder of Turning Point USA, a conservative organisation with branches on university campuses across the US. Originally something of an alternative to Campus Republican chapters, TPUSA were backers of Donald Trump, an outsider presidential candidate.

TPUSA utilised new media, creating content by Kirk touring campuses and challenging liberal and left-leaning students to debate him. Of course, the edited videos that appeared online always showed Kirk ‘winning’ the debate with his adversaries. In the article I was writing I described Kirk’s ‘debate me’ style as epitomising the methods of what we used to call the alternative right. When I wrote that sentence I released that we no longer call it the ‘alternative right’ as what was once an alternative was now the mainstream.

Trump is now in his second term, surrounded by people who share his ideology. Kirk’s TPUSA has become something of a media empire, and he died a multimillionaire.

So let’s take a step back and look at how things got to this point.

The term ‘alternative right’ was coined by the white nationalist Richard Spencer in 2010 and was something of a euphemism for ‘far-right’ with its connotations of racism and anti-semitism. Although Spencer himself has done little to distance himself from those beliefs, the phrase alternative right or ‘alt-right’ did catch on. Steve Bannon, later an advisor to Donald Trump but at the time the CEO of Breitbart News, described the news outlet as ‘the platform for the alt-right’.

Brietbart was also known for ‘the Brietbart doctrine’ the idea, as stated by founder Andrew Breitbart, that “politics is downstream from culture” and to change politics you first change the culture. It’s not an entirely original concept. Some of you may be familiar with the concept of hegemony, from the Italian Marxist thinker Antonio Gramsci. This is the idea that the ruling class in society maintains power though cultural and ideological leadership as well as through force.

Counter-hegemony, developing cultural and ideological leadership in opposition to those in power, is not just a strategy that can be used by Marxist readers of Gramsci however. Alain de Benoist, a founding member of the French novelle droite or ‘new right’ advocated for those in his movement to become “right-wing Gramscians”. In his 1977 work The View from the Right de Benoist wrote that the French Right

“Has not grasped the significance of Gramsci. It has not seen how cultural power threatens the apparatus of the state”. While de Benoist, who is still alive, doesn’t identify as part of the alternative right, his work has been an influence on the movement.

The term ‘alternative right’ also served as an alternative to the neoconservatism of the George W Bush years that defined politics in the US for most of the previous decade. While Bush and the Republican Party were electorally successful throughout the 2000s, the 2003 invasion of Iraq saw massive street protests around the globe, along with widespread opposition to the erosion of civil liberties. For my generation growing up in that time, listening to the politically charged lyrics of popular rock bands like Rise Against and System of a Down, being a conservative or right leaning young person would have been deeply uncool. You could say the left was at that time winning the culture war, although it didn’t actually translate to electoral success.

We can define that era of politics as bookended by the 9/11 attacks and the global financial crisis of 2008. Bush was succeeded by Barack Obama, who ran with the slogan of ‘hope’. But hope didn’t seem to last long as the Obama era saw little in the way of real political change. In 2011, a mass protest movement began and spread throughout the world. Beginning with unemployed and underemployed youth in North Africa in what was soon labeled the Arab Spring, spreading to Southern Europe with the indignados, or indignant ones, then to the English speaking world where the moniker ‘Occupy’ was used after the Canadian magazine Adbusters put out a call to ‘Occupy Wall Street’

When Donald Trump was elected president of the US in 2016, I commented that it will be the job of historians to answer the question of how in just five years we went from a massive populist movement highlighting the widening gap between rich and poor, to the election of a New York City real estate mogul. A decade on it doesn’t actually look like a difficult question any more.

While in North Africa the Arab Spring had toppled governments, in the West, Occupy had little in the way of successes. Much of the energy of Occupy was channeled into the campaigns of social democrats like Bernie Sanders in the US and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, campaigns arguably thwarted by the establishments of the Democrat and British Labour parties respectively.

Young people who had been born into an era of neoliberal restructuring and came of age during the global financial crisis, faced a future where they would be the first generation since the second world war to be economically worse off than their parents. This wasn’t true for everyone, if your parents were immigrants to the west, or they were African Americans born in an era where segregation still existed in much of the US, you might be doing better than them. But it was especially true for whites without a university degree, and many others were finding a degree wasn’t the ticket to the middle class they had thought it was.

Many millennial men in the 2010s had given up on hope, living with their parents well into adulthood and with precarious work if they had work at all, retreating into fantasy worlds of video games and pornography, spending most of their waking hours online.

The Internet has long been a haven for far-right ideology. While today the idea of “no platform for fascists” is seen as a censorious left-wing position, it was the policy of almost all print and broadcast media following the defeat of Fascism in the second world war. The early pioneers of the Internet however adhered to a libertarian ethos which has been dubbed ‘The Californian Ideology’ influenced in equal parts by the social movements of the nineteen sixties and the neoliberalism of the nineteen eighties, the utopian belief was that the global network of computers that made up the internet would bypass traditional media gatekeepers, there would be no censorship but the best ideas would win out in a virtual world where equal access would collapse traditional inequalities between class, race and gender.

The lack of gatekeeping meant that the far-right were early adopters of this new communication technology. The white supremacist forum Stormfront began in 1995, before many people knew what the internet was, and even before the world wide web there were dial up bulletin boards where a user could engage with holocaust denial and conspiracy theories. Stormfront connected people who already held far-right views but it was unlikely someone who didn’t already hold those views would end up there, so users encouraged each other to spread their views on the wider web.

The Californian Ideology was in the ether when Christopher Pool founded 4chan in 2004. A discussion board where users could post anonymously, threads with new engagement would be pushed to the front pages of forums, and when low engagement pushed them off the last page, they would disappear. Moderation was lax and little was censored. When a political discussion forum was started, Pool himself noted that it had essentially become a copy of Stormfront.

It was on 4chan, among these disenfranchised and extremely online young and predominantly white men, where the harassment campaign known as #Gamergate began. This campaign targeted women associated with video game journalism and in particular a woman who had a sizable following for a YouTube channel where she examined video games through a feminist lens. These men had taken on the belief that their lack of economic and also romantic success was not the consequence of neoliberal capitalism, but instead the result of social gains by historically marginalised groups such immigrants and the LGBT community, but more than anything else, the fault of feminism.

A woman subjecting video games to the same kind of feminist analysis that gets applied to film and other media was seen as an encroachment of feminism into one of the last remaining masculine spheres of life. The potential of these angry young men as a political force was recognised by people like Steve Bannon who told a biographer “You can activate that army. They come in through #gamergate or whatever, then they get turned on to politics and Trump”

Dale Beren’s book It Came from Something Awful: How a Toxic Troll Army Memed Trump into Office is a great read on this topic.

The tactic of mass harassment coordinated online to push people, especially women, out of public life for advocating political ideas that the right objects to, has become common the world over. For local examples, think of what has happened to Golriz Gharamhan, Tory Whanau, and Benjamin Doyle to name just the most well known recent cases. Harassment campaigns are tacitly abetted by groups like the Free Speech Union who, rather than speaking out for the people whose speech is being silenced by harassment, oppose any legislative changes that would make social media platforms more responsible for providing the tools to coordinate these campaigns, and have even opposed updates to the Harmful Digital Communications Act that would give victims more redress against their harassers.

I’d encourage people to seek out the articles written by Cassandra Mudgeway, a senior law lecturer at Canterbury, if you’re wanting to know more about the issue of gendered violence facilitated by social media and the internet.

On the topic of social media, platforms like Facebook and YouTube bear some responsibility for the state of the world today. The development of algorithms designed to keep someone on a website for as long as possible, in order to expose them to more advertising, led to people being fed increasingly hateful or conspiratorial content that would elicit strong emotional responses and keep them watching.

It wasn’t a decision by these companies to promote the hard right, but an amoral drive for profit that many far-right political actors, like Charlie Kirk who I mentioned at the start of this talk, realised they could take advantage of. It also gave rise to the phenomenon of ‘masculinity influencers’ who could peddle self-help advice to the angry young men swept up in the right, people like Jordan Peterson who promoted reasonable advice like keeping your living space clean, with a deeply conservative worldview that postulates there is no structural oppression, only a natural and everlasting ‘dominance hierarchy’ that men should strive to reach the top of, stepping on whatever groups they need to on the way.

The younger generation of men are being exposed to even more extreme ideas through social media. The award winning British drama series Adolescence recently drew attention to this problem, and in this country we recently saw teachers unions raising the alarm about radicalised young men who they encounter in the classroom.

Social media also captured the advertising market that had previously sustained journalism. New Zealand has fewer professional journalists today than we did twenty years ago, despite our population growing by a million people in that time. Right-wing shock jocks and outright disinformation spreading outlets are increasingly filling the void, as critical journalists find themselves subject to #gamergate style harassment when they report on the far-right.

When Twitter took some responsibility for the harm their platform had facilitated, removing a large swathe of far-right accounts following the insurrection of January 6 2021 when supporters of ousted president Donald Trump disrupted the peaceful transfer of power, it began a chain of events that led to Elon Musk, the world’s richest man and a backer of not just Trump but far-right parties globally, including the Nigel Farage led Reform party in the UK and the AfD in Germany, purchasing the platform for $44 billion dollars.

Musk called himself a free speech absolutist, reinstated the banned users including Trump (who meanwhile had started his own social media platform), fired staff responsible for dealing with issues of disinformation and election integrity, and removed almost all content moderation policies. Within a year the value of the company was less than half of what Musk had paid for it, as advertisers did not want their marketing materials appearing alongside the increasingly commonplace racism and anti-semitism. It was a bad business investment, but Musk was not buying stock, he was buying hegemony. That said, the value of Twitter, which he has since renamed X, has actually crept back up to what he paid for it in 2022 as of earlier this year. Possibly reflecting that being associated with hateful views isn’t as damaging to a brand as it once was.

Stepping back a few years, it would be irresponsible to talk about the modern right without talking about the COVID-19 Pandemic. The lockdowns that accompanied the pandemic meant people were spending a lot more time online, susceptible to the COVID related disinformation spreading via those same social media algorithms that had spread far-right ideology. Indeed conspiracy theories from the far-right were cross-pollinating with conspiracy theories related to the virus and the vaccine, and bringing people interested in alternative medicine and wellness, ideas that we’d once perhaps have associated with the political left, into what Naomi Klein described as an alliance of “the far-right and the far-out”.

Commentators and others, including the World Health Organisation, have spoken of an “infodemic”, an outbreak of false and misleading information that spreads parallel to a disease outbreak. While the term is useful, and one I’ve used myself, it is somewhat contested. Claire Birchall and Peter Knight in their book Conspiracy Theories in the Time of Covid-19 write that rather than focusing only on the present conditions, “it is important to situate the so-called infodemic that accompanied Covid-19 within other, slower crises that concern attacks on equality, social democracy, the welfare state, democratic institutions and expertise.”

They cite journalist Jeremy Gilbert who suggests that the erosion of social welfare has led to a disbelief in the possibility that public institutions could be supportive or even merely benign. Gilbert sees this disbelief that the state can be anything other than conspiratorial as inevitable once its function has shifted from protecting people from the worst excesses of free market capitalism, to instead exposing people to them.

After four decades of living under a mode of rationality that minimises or denies the role of the state in providing some kind of social security, the financial and social packages offered by many governments as part of the response to the economic fallout from the pandemic put lie to the neoliberal insistence that “there is no alternative” to free markets, privatisation and individualism, raising suspicions about the state’s motives- suspicions fueled by the fact that such support was accompanied by the necessity for people to make sacrifices concerning certain freedoms.

So that’s the background to the modern far-right. In this country, we saw the disparate groups that this situation had birthed come together in the occupation of parliament grounds in the early months of 2022. Taking credit for half the people at that protest was Voices for Freedom, an anti-vaccine group founded by former candidates for Billy Te Kahika and Jami-Lee Ross’s Advance New Zealand Party.

After the protest Voices for Freedom, wholeheartedly embraced the Breitbart doctrine, launching not a political party but a media outlet, initially called Reality Check Radio and today usually referred to as RCR Media. Broadening in scope beyond anti-vaccine beliefs, RCR spreads climate change disinformation and on one show, hosted by the former general secretary of the New Conservative Party Diewue de Boer, even the ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory that posits there’s a plan to replace western populations with non-white, often muslin immigrants. This of course, is the theory the Christchurch shooter named his manifesto after.

The so-called ‘Freedom Movement’ formed a mutually beneficial relationship with New Zealand First, who had been ousted from parliament at the 2020 election but crossed the 5% threshold again in 2023, with a party list populated with prominent anti-vaccine activists and former members of the New Conservatives and other fringe parties. Winston Peters, the only prominent politician to meet with the protesters occupying parliament grounds, launched his 2023 election campaign on Reality Check Radio.

Dieuwe de Boer wrote that Peters had made a “masterstroke” by recruiting a “freedom movement star” referring to the anti-vaccine activist Kirsten Murfitt, who at number 11 on the list was within a stones throw of actually winning a seat. de Boer noted that “NZ First has always had a solid base of 2-3% who will vote for Winston no matter what, and so its path to victory only requires it to pick up an additional 2-3% of the votes” They found that 2-3% in the far-right.

Since the election, New Zealand First (and to some extent ACT, also influenced by the far-right’s counter-hegemony campaign) helped mainstream numerous political ideas that were once confined to the fringe. Following the signing of the coalition agreement between National, ACT, and New Zealand First, New Conservative Party leader Helen Houghton appeared on RCR Media and described the agreement, which made numerous New Conservative Party positions on LGBT issues government policy, as “like a Christmas present” telling the host she actually shed some tears of joy.

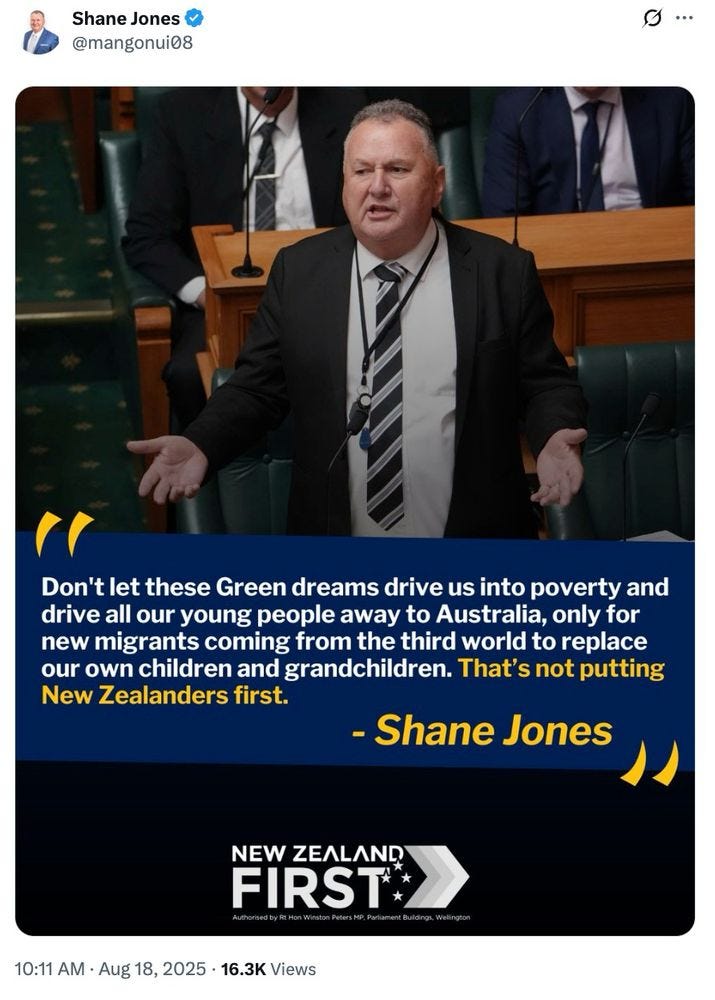

When interviewed by RCR Media at the party conference, NZ First deputy leader Shane Jones suggested trying to stop climate change was “woke folly” and last August echoed the Great Replacement conspiracy on X sharing a quote from himself suggesting that migrants are “coming from the third world to replace our own children and grandchildren”.

So we no longer speak of the ‘Alternative right’ because what was once alternative is quickly becoming the status quo.